The Nine Circles of Dependency Hell (and a roadmap out)

Your project has been overwhelmed by the complex web of its software dependencies to the point of stoppage. We spend more time fixing these dependency issues than writing code most of the time. Every developer has been there.

Welcome to the Nine Circles of Dependency Hell; I’ll be your Virgil.

The First Circle: Limbo. Are my dependencies even correct?

Each circle represents a more evil transgression of package management. In the first circle are those who committed updated packages without recording them.

Most language package managers suggest that you don’t check in a node_modules or vendor folder anymore. But there can still be inconsistencies between the packages in use and a package manifest like packages.json or go.mod—a developer uses a new dependency without explicitly adding it, or removes one without removing it from the manifest.

Make sure you’re running a check against this in your presubmit. Before the pull request is merged is also a great time to vet new dependencies—for licenses or security issues. For example, the bouk/monkey package on GitHub has a license that explicitly forbids anyone from using it!

The Second Circle: Lust. You will stop at nothing to depend on that new package.

Here wander those who will chase any dependency without vetting it. It might not have documentation, it might not have been updated in years, but for some reason, it calls your name to call its functions. We all want that new function, that latest version of the library.

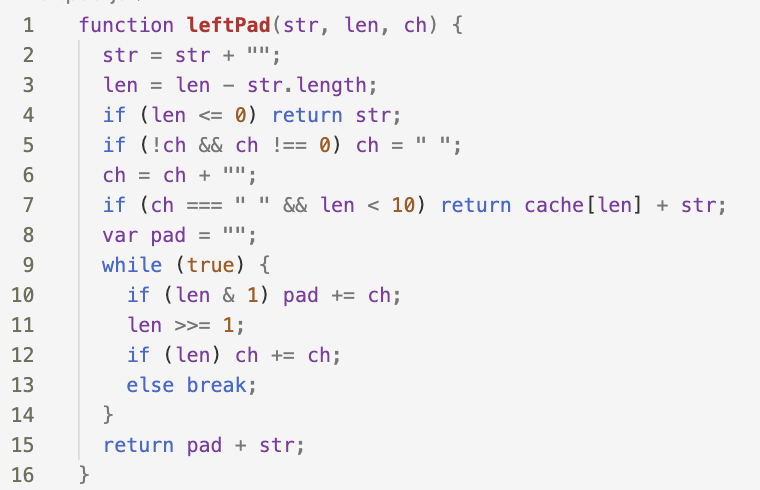

Package lust is not without punishment. When the author of the left-pad JavaScript library decided to remove the package from npm, thousands of projects broke, including large ones like Node and Babel. What if the author had uploaded malicious code instead? Sometimes a little duplication is better than a bit of dependency.

The Third Circle: Gluttony. Bloated bundles. Too many dependencies.

One more dependency won’t hurt until it does. Slow builds and massive repositories are symptoms of too many dependencies.

Instead of eating more dependencies, try to snack on the low-hanging fruit of removing unused dependencies (First Circle) as a good starting point. Then, use static code analysis tools to determine where your most significant dependencies come from and determine whether or not you can slim them down or remove them. One example is to only import what you need from the code (e.g., no star (*) imports)). Importing only what you need might not always reduce your bundle size, but will almost certainly clear up your global namespace so that you avoid potential conflicts.

The Fourth Circle: Greed. Multiple package managers.

Your data scientist loves to use anaconda, so now there’s a conda configuration file checked in alongside the pip requirements.txt. Two’s company.

The only option here is to have a single source of truth per language. Of course, you’ll most likely need multiple package managers along the way: OS-level package management like apt, pacman, and different package managers for other languages. How do you manage all these layers of packages? Tools like Docker can help capture all of these in one place, all in a mostly reproducible manner.

The Fifth Circle: Wrath. The package or version you need isn’t in your package manager.

Now that you think about it, you’re using Ubuntu Trusty Tahr. Didn’t it reach end of life in 2019 (it resides in a different place in Dependency Hell)? So, where are the package owner gremlins that are supposed to add it?

There’s a simple way for most language-level package managers to reference a specific Git repository and commit.

For npm, you can simply do

npm install git+https://github.com/organization/repository.git#commit

For Go modules, you can do

go get github.com/organization/repository@commit

If you can, point to a tag. For operating system packages, you can be a good open source citizen for operating system packages and contribute the package to your package manager of choice. If that’s untenable, many projects simply copy the code into a special folder (at Google, it’s usually called third_party) along with the licenses. Make sure you have a way of capturing the versioning information—what commit was the code pulled? Where does the upstream code live?

The Sixth Circle: Heresy. Monkey patching a dependency.

Why won’t this open source project take my specific and untested patch? Guess I’ll just monkey patch it.

Usually, monkey patching is a terrible idea. First, it makes code difficult to upgrade. Second, patches are difficult for others to discover (how do you know what’s been changed?). If you really must do this, using the third_party folder is one potential escape hatch. Just make sure you don’t use the bouk/monkey library from the First Circle!

The Seventh Circle: Violence. Breaking changes on a minor or patch version.

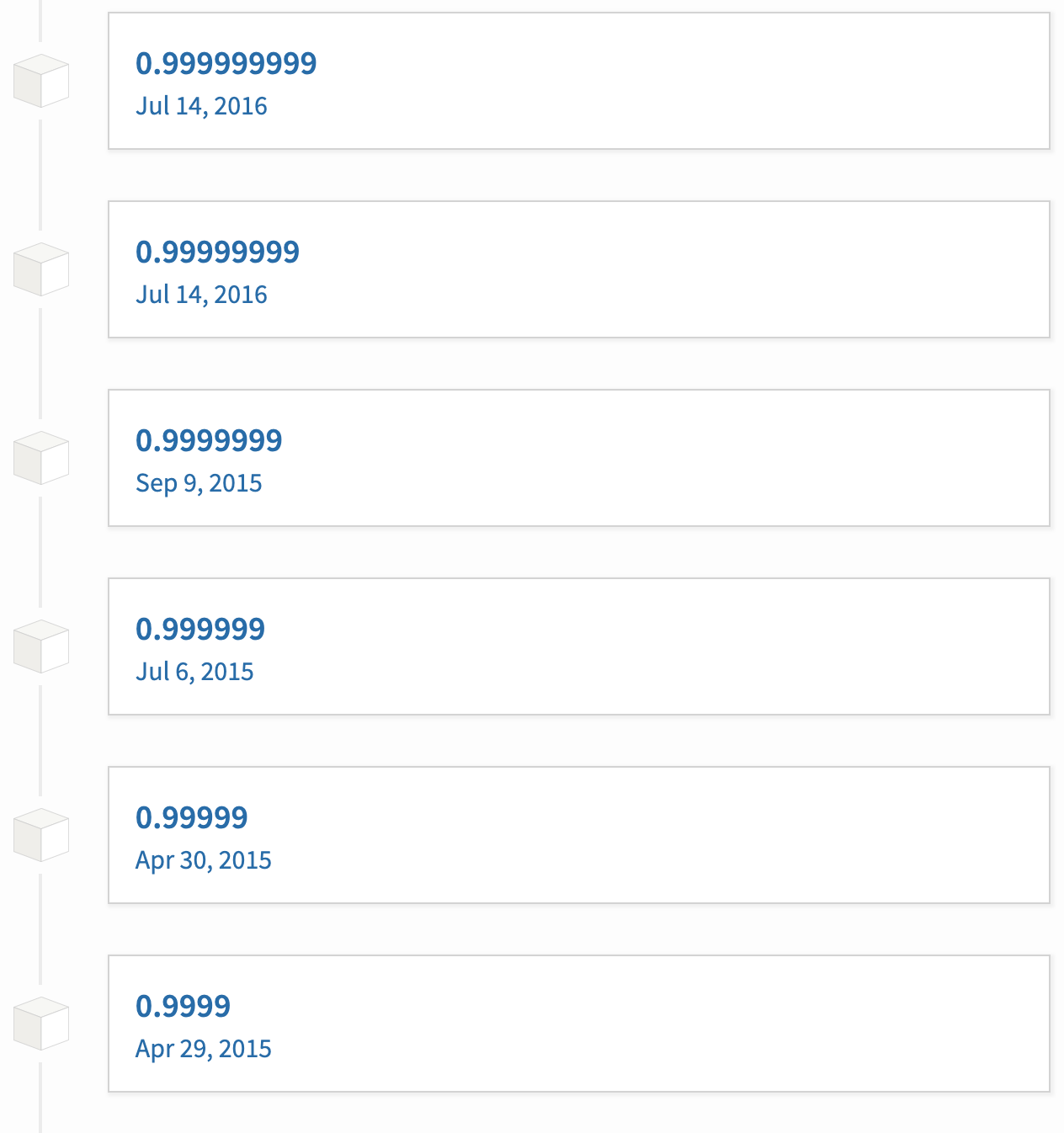

In theory, it should follow major.minor.patch. In practice, the developer used a pseudo-random number generator. Version is open to interpretation—a popular Python package, html5lib, previously versioned its packages asymptotically: 0.99, 0.999, 0.9999, and so on.

What is semantic versioning? From the Semantic Versioning documentation:

Given a version number MAJOR.MINOR.PATCH, increment the: MAJOR version when you make incompatible API changes, MINOR version when you add functionality in a backward-compatible manner, and PATCH version when you make backward-compatible bug fixes. Additional labels for pre-release and build metadata are available as extensions to the MAJOR.MINOR.PATCH format.

It’s hard to follow semantic versioning—it takes significant effort to make backward-compatible changes, backward-compatible bug fixes, and to backport security patches to old release numbers. However, following semantic versioning is the best way to spread joy to your downstream users.

The Eighth Circle: Fraud. Circular dependencies.

Library A depends on a specific version of B, but B can’t run without depending on a particular version of A.

Circular dependencies often come from overeager package splitting. We believe that different components should be logically separated, but they are tightly intertwined.

Another cause of circular dependencies is a common dependency on types. Can you split out the types into a separate package? Finally, consider using interfaces, contracts, or dependency injection to provide loose coupling across different packages.

The Ninth Circle: Treachery. The diamond dependency problem.

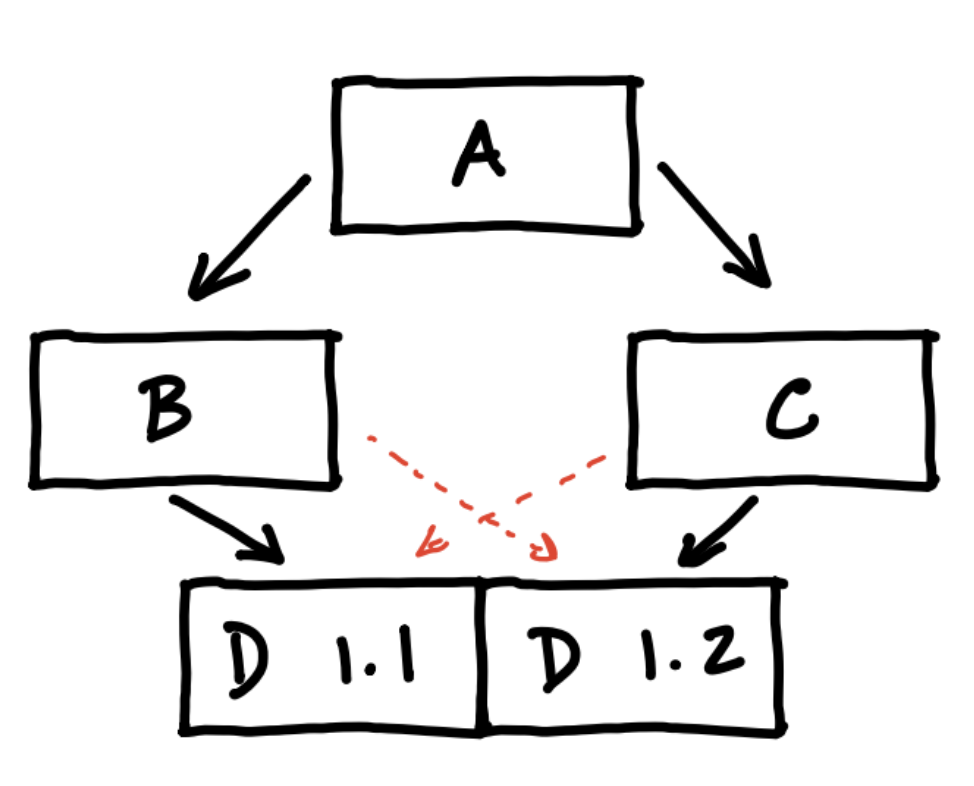

Library A depends on libraries B and C, and both B and C depend on D—but B requires D version 1.1, and C requires D version 1.2.

The diamond dependency problem is reserved for the deepest circle of Dependency Hell because it is so difficult to fix. You can’t fix the problem in either Library A (which you most likely control) or Library D. The issue must be resolved in the intermediary libraries, B or C—which previously didn’t believe they had any relation other than a shared dependency.

How do package managers solve this problem?

The diamond dependency problem is NP-complete (read: can take a long time to solve, even for computers) for most implementations. There are two ways to shortcut this complexity. First, you can simply allow two different versions of D. This works for some cases but doesn’t make sense for others. This resolution method is how most JavaScript package managers (npm and yarn) work. As a result, you can end up with many different copies of the same library, just at different versions. Other languages, like Go, only let you specify the minimum version of a dependency. If Go detects two different versions of the same dependency, it will attempt to use the newest minor version according to semantic versioning. If neither package shares a major version, it will error. (You can fix this by adding the major version to the import path).

If you’ve made it this far, you have seen the darkest circles of Dependency Hell and you have the tools you need to get your team out of treacherous territory and back to shipping products.

As a recap:

- Verify that the actual dependencies match the recorded dependencies in a pre-submit test.

- Sometimes, a little duplication is better than a little dependency.

- Use a single package manager. Use declarative tools to glue everything else together.

- Know that you can tie a dependency to a specific commit if it comes down to it.

- Avoid monkey patching. If you must, use a third_party directory.

- Follow semantic versioning as much as possible.

- Resist the temptation for over-eager package splitting. Tightly intertwined dependencies should be in the same package. When you can’t, use interfaces, contracts, and dependency injection.

- Understand how your package manager resolves the diamond dependency problem.

About the author

Matt was previously a software engineer at Google working on Kubernetes. Currently, he’s working on a new startup. He writes daily posts on engineering and startups on his blog, matt-rickard.com, where a version of this post originally appeared.